Prof. Jon Baggaley Athabasca University |

M-learning how to M-teach J.P. Baggaley |

|

Abstract Mobile learning methods offer

valuable possibilities for students in remote

and distant parts of the world. The article

argues, however, that the promise of

"m-learning" will not be fully realized until

educators learn to "m-teach", experiencing their

remote students' problems for themselves. The

inaccessibility of common online methods in

distance education (DE) is discussed, and the

unreliability of standard online methods across

extreme distances. The need for universal

recognition of the value of online audio and

video-conferencing in DE is argued, and the

importance of developing social protocols in the

selection and use of collaborative tools in

specific online situations. Introduction After 25 years of teaching educational media on the traditional university campus, I moved into distance education (DE). Although I appreciated the opportunity to teach via the media on a daily basis, I rapidly regretted the lack of direct contact with students, and the computer console's claustrophobic solitude. In the late '90s, I added online audio-conferencing elements to my courses, and more recently interactive video elements. Using a network of old 486 PCs, I developed a basement "studio" at my home, with graphic special effects which allow me to discuss visual presentations with my students around the world, using online conferencing freeware (Baggaley, 2004, 2005). In 2003, I packed these methods into a laptop computer in order to be able to maintain my DE work from "on the road". An opportunity to practise this "mobile teaching" approach arose between December/2003 and May/2004, when I visited 12 Asian nations (Bhutan, Cambodia, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Laos, Mongolia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) to conduct a review of current Asian DE methods. The tour revealed a series of contrasting styles of teleconferencing usage in Asia, and ways in which the skills and specialties of different regions can be combined to create a 21st-century, transnational DE approach (Baggaley & Ng, 2005). The tour also demonstrated how truly "placeless" modern DE has become. From urban and rural parts of Asia, I maintained my daily commitments to my students and colleagues, using a variety of dial-up, broadband cable, and wireless connections - via e-mail, instant messaging, video-conferencing, web-casting, and other Internet audio methods. I supervised student projects and theses from hotels, airports and Internet cafés, and took part in the usual routine of university staff and committee meetings, all at little or no cost. The tour also yielded some surprises about the deficiencies of online delivery methods that distance educators commonly take for granted.

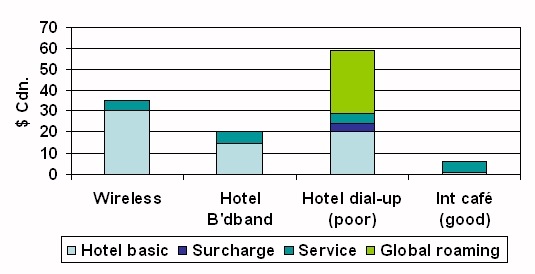

Mobile technologies are touted as a breakthrough in distance education, providing impressive new levels of flexibility for the student (Keegan, 2002). Short messaging services (SMS) can be used to access automated course delivery materials and grades, while personal digital assistants (PDAs) offer the student a wide range of audio, video and text communications with the teacher and other students. In my Asian tour of current educational technology initiatives, I heard constant discussion of these new technologies (Rao, 2004), and saw numerous imaginative applications of them under development, notably in the open universities of Indonesia and the Philippines. By contrast, in North America the DE possibilities of the new mobile devices seem barely glimpsed. The new technologies are not so widely used there, probably because traditional telephone calls are inexpensive. The flat-rate costs of telephone calling in the US and Canada may have removed the urgency from exploring the newer media as cost-effective communication options - with the result that many N. American distance educators remain loyal to "the devil they know", the old one-on-one, telephone-tutorial and correspondence approaches. E-mail and online text-conferencing have added an electronic face to these older methods, but little has changed in the mindset of DE teachers who have been communicating with their students by letters and the telephone for thirty years. In Asia, on the other hand, the high cost of telephone calling has spurred innovative approaches to DE that are generating numerous synchronous and multi-party collaborative techniques. In every Internet café on the continent, it seems, the versatile freeware Yahoo Messenger is installed, with its capacity for text, audio and video-conferencing among up to 40 participants; and thousands of students are now using the remote Internet cafés of Asia in access their degree course materials at the world's "mega-universities" (Daniel, 1998). These tools are made more accessible through the common use of hand-held personal digital assistants (PDAs), combining voice, e-mail and web functions. The term "online technology" has a very different meaning in the Asian context compared to that of N. America. For example, at the Indian mega-university, Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), "online" represents a total convergence of all media on the Internet, with the mandated objective of "Education For All" of India's billion inhabitants. Distance educators in N. America, by contrast, tend to consider online processes more in terms of relatively limited, text-based teaching methods. I was able to compare the costs and efficiency of a wide range of access methods during my Asian travels, in the course of maintaining contact with my students and teaching colleagues in Canada. Figure 1 compares the costs of dial-up, broadband and wireless connections available to today's traveler in hotels, airport lounges, and in the ubiquitous Internet cafés and kiosks. There is a simple pattern to the varying costs of Internet access between countries. The more affluent the country, it seems, the more impossibly high the costs of an online connection. For example, an hour's wireless access in an airport lounge can cost $30 per hour in an advanced economy such as Singapore, while being available for $5 per day to the guests of a 3-star hotel in Laos. In affluent countries, a free wireless connection may easily be located during one visit, and yet be restricted to subscription customers a month later, with rates in the range of $20 per hour. Meanwhile, in remote rural parts of Asia, efficient audio-conferencing is available free of charge on the slowest of 19 kps dial-up connections, by means of locally developed high-compression techniques. In the centre of the Mongolian Gobi desert, for instance, I saw a dial-up connection used by doctors to share diagnoses of their patients' X-rays, with text/audio discussion enabled by the ubiquitous Yahoo Messenger. Across the board, however, broadband cable access points currently provide the most reliable and economical of DE access; and high-quality, cost-free video-conferencing is gaining ground among Asian DE teachers and students, who use the new collaborative and messaging tools with an easy spontaneity. They naturally gravitate to the more than adequate freeware and open source software (OSS) that is available for these functions; and their institutions have no time at all for the outlandishly priced commercial solutions hawked to them by 1st-world distributors. The commercial software vendors of the world are in for a rude awakening indeed, as the "developing" world surpasses them with its superior, home-grown, OSS alternatives.

A Day of Reckoning Not only are the DE software vendors of the 1st-world living in something of a fool's paradise at present; so are the DE teachers. Judging by common DE practice, they seem to have little or no awareness of the DLT strides being made elsewhere - not just in Asia but also in Europe, where "voice over Internet protocol" (VOIP) methods have rapidly taken over from the costly telephone-based conferencing alternatives during the past four years. The Canadian understanding of "m-learning", for example, is rudimentary compared to that of the Philippines -described by BBCWorld (25/March/04) as the "text-messaging capital of the world", with 22 million cell 'phone users sending an average of seven SMS messages per day. Unfortunately, it is not likely that Canadian educators will gain competitive insights into these options, living as they do in a society where the technologies are not extensively used. New devices integrating voice, e-mail and web functions are burgeoning; yet, at the time of writing, the latest BlackBerry gadget providing these functions (the 7100t PDA) has not yet arrived on the Canadian market. Many distance educators also lack direct experience of the problems and high costs of online access in remote parts of the world. A good way to get such experience is to be obliged to establish regular online access in maintaining one's attendance at university meetings in N. America, from hotel rooms and Internet cafés in Bhutan, Cambodia and Vietnam, and in order to respond to students' questions without making them wait until one's return to the office weeks later. Yet a current Google search yields only 2,010 references to "mobile teaching" compared with 28,200 to "mobile learning". This lesser emphasis on "m-teaching" may partly be due to the reluctance of DE institutions to sanction the break with tradition that "m-teaching" represents. It is ironic, therefore, that N. American DE institutions vigorously promote themselves to developing-country students, and are proud to publicise the number of countries from which their courses are taken. It is also somewhat naïve of these institutions to think it sufficient to teach their international students using the methods they have developed to teach their US and Canadian students: e.g. e-mail and web-based text-conferencing. Until directly experiencing the situation of Asian distance learners, I too had assumed that web-based and e-mail methods are appropriate for DE worldwide. This notion was rapidly scotched when I watched a DE student in Bhutan press the "Get E-mail" button and turn patiently to other work during the hour it took the message to download. From Mongolia, I sent graded assignments to 25 international students by e-mail attachment, and waited for two minutes while each one was transmitted. Batches of more than three e-mails at a time invariably failed to transmit; and I had to send the each of the 25 e-mails five times before I could tell that every student had received them. Not all Asian countries are equally advanced in their development of innovative new delivery technologies. I also experienced the frequent impossibility of accessing the web-based materials on which the courses of my Canadian university department are based. A major reason for these problems is the often tortuous routings of e-mails and web-based materials between Asian students and their N. American teachers. At the time of writing, for instance, a web server request between the open universities of Canada and Indonesia, goes through 17 server "hops" in 5 cities (Figure 2), and e-mails between the two centers are regularly "bounced back". Again, N. American educators will have a major surprise when the DE institutions of the supposedly undeveloped world give up on these methods, and capture the international student market with techniques that enable superior communication via online messaging, audio-conferencing, and webcam media - techniques that give no problem at all over the 10-cents-per-hour broadband connections of Internet kiosks on every Asian street corner. Substantial proportions of N. American students live in remote and distant contexts too, which is the very reason they were drawn to DE in the first place. Why should they remain loyal to educational institutions that cling stubbornly to technologies which fail to communicate optimally with them?

In fact, many N. American DE providers do not even begin to consider their students' technical needs. How many online teachers, for example, ever ask their students about the computer facilities and access connections at their disposal, let alone design their teaching methods to cater to them? For example, the Bhutan student mentioned earlier could be advised to communicate with his teacher via messaging techniques instead of e-mail; and students with only 128k RAM in their computers could be recommended to use the Yahoo Messenger audio-messaging application for this purpose, rather than the more elaborate applications requiring more RAM. Check techniques such as "trace-route" should be standard in the preparation of every virtual classroom, but they are not. (One such tracing tool, "VisualRoute", was used to collect the data of Figure 2.) Many online DE delivery methods are employed on the blind assumption that the students are receiving and comprehending, while the students themselves innocently assume that failures to receive the course materials and information must be the fault of their personal computer illiteracy. The lack of concern for students' facilities on the part of many online teachers is essentially no different to inviting students into the classroom, locking the door before they arrive, and refusing to give them the key. Even if DE students do not have online access problems, their teachers cannot expect them to be satisfied with styles of teaching that emphasize e-mail and other asynchronous methods to the exclusion of other options. With a typical online class containing 30 students, it is impossible for the teacher to do constant justice to all of them via text-based methods alone. In teaching online courses where e-mail and text conferencing have been the main communication options, I have needed to send more than 2,000 individual e-mails and conferencing postings over 13 weeks. Inevitably, these messages often have to be terse. Responding in detail to graduate-studies level questions involves a heavy weekly writing load. The same amount of information can be covered in a single hour via online audio-conferencing methods; and my solution to these logistic and educational challenges has been to make a battery of online messaging techniques accessible to all members of the class. At the beginning of each course, I determine the equipment and access speeds that each student uses (Depow et al., 2003). This information allows me to assist in diagnosing connectivity problems. I also request that my students follow specific protocols in order to optimize online communication with me. For example:

Such disciplines are essential in online education, be it mobile or static. They help the teacher to maintain the workload, and they remind the students that the teacher is dealing with many of them simultaneously, and has to structure the working day in the same way as a physically-present teacher does on campus.

Conclusions Recent visits to 12 Asian countries have yielded some salutary insights into the problems faced by DE students in attempting to receive and respond to their online course materials. DE providers in the 1st world are failing to serve their remote students in their selection of appropriate online technologies. E-mail and web-based techniques are unreliable as media for communication at extreme distances and with remote locations. In many parts of the world, the costs of private Internet connections are prohibitive, whereas Internet cafés on every street corner provide cheap and reliable messaging ("texting") and synchronous conferencing solutions, which are fast becoming the educational delivery systems for millions of students at the world's DE "mega-universities". The shift towards mobile educational techniques ("m-learning") is a valuable step towards addressing the problems of remote learners. In order to design teaching methods that take advantage of m-learning technologies, however, distance educators must first obtain a greater understanding of their remote student's access problems, by learning how to deal with the challenges of "m-teaching". Ultimately, the m-teacher and the m-learner will be able to maintain their interactions effectively via laptops well stocked with online VOIP and A/V-conferencing software. They will do this as easily and cost-effectively when "on the road" as from their home offices. [This paper is a modified version of a presentation to the 4th Annual Conference of DIVERSE, held at InHolland University, Diemen, the Netherlands in July 2004.]

References Baggaley, J. P. (2004). Video-conferencing from the Basement and the Suitcase. 4th Annual Conference of DIVERSE, held at InHolland University, Diemen, the Netherlands. Baggaley, J. P. (2005). Live…from my basement studio. DIVERSE Newsletter 2 (in press). Baggaley, J. P. & Ng, M. (2005) PANdora's Box: distance learning technologies in Asia. Learning Media Technology 1(1) (in press). Daniel, J. (1998). Mega-universities and Knowledge Media: technology strategies for higher education. London: Kogan Page. Depow, J., Klaas, J., Wark, N., & Baggaley, J.P. (2003). Issues affecting Canadian participation in online audio conferencing. Communiqué. Retrieved September 19, 2004, at http://www.cade-aced.ca/dynamic/en_communique_article.php3?key=22 Farrell, G. (2003). COL LMS Open Source. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning (COL). Retrieved September 19, 2004, at http://www.col.org/Consultancies/03LMSOpenSource.htm Keegan, D. (2002). The Future of Learning: from eLearning to mLearning. Hagen: FernUniversitat. Rao, M. M. (2004). Asia Unplugged: learnings from the wireless and mobile media moom in the Asia-Pacific. Retrieved September 19, 2004, at http://www.indiasage.com/asia_unplugged.asp

|

|

|

|